What can we, as mental health consumers and professionals, learn from American infrastructure and engineering? Maybe your answer is regulation - we need oversight boards and accreditation and licensure. That might be right under the surface. After all, what does a collapsing oil rig, or a hydrogen fluoride (HF) gas release have to do with talk therapy? I believe the parallels are more literal than expected. The failures of engineering are a sobering reminder of the stakes of our systems and infrastructure throughout American culture, including mental health treatment.

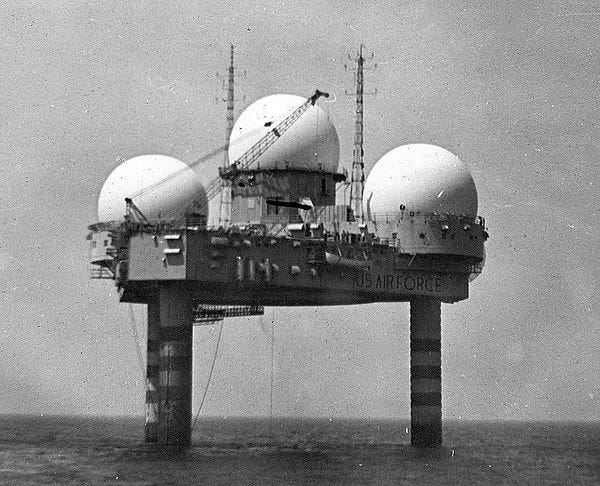

Texas Tower 4 - Radar Station

Destroyed in a winter storm 1/15/1961, 28 fatalities

Defining a Profession

Abraham Flexner infamously asked “is social work a profession?” in 1915, to the chagrin and eternal attention of social workers. This article has been interpreted and reinterpreted over the ages and I will spare you a nuanced debate on what he meant.

I want a moment to simply bring this quote to your consciousness:

“The word profession or professional may be loosely or strictly used. In its broadest significance, it is simply the opposite of the word amateur. A person is in this sense a professional if his entire time is devoted to an activity, as against one who is only transiently or provisionally so engaged” (Abraham Flexner, 1915).

In this context, a professional is merely the opposite of an ametuer - expertise is the key that sets you free! Formalizing a single realm of focus with other experts sets the stage for a profession.

He then argues that a profession includes 6 main criteria:

It involves intellectual operations with large individual responsibility (requires deep thinking and responsibility, complex problems and important decisions.)

They derive their raw material from science and learning (not just guesswork and tradition.)

The material they work up to a practical and definite end (knowledge is applied to clear, practical results.)

They possess an educationally communicable technique (it can be taught and passed down.)

They tend to self organize (there are associations, standards, and guidelines.)

They are increasingly altruistic in motivation (benefits society, not just to make money.)

Under these terms, both engineering and mental health would squarely fit the bill for someone looking to check the boxes. We could debate how well that glove fits, but instead, let’s assume they are both professions by Flexner’s unpopular standards.

Standards, Shmanders

As a college instructor, I spend a lot of time trying to get students to understand the stakes of the work we do trying to help people better their lives. Usually, students take this very seriously. However, recently, I’ve been hearing a lot of questions like, “Prof. Murphy, you talk about how bad an expensive HIPAA violations can be - but how come the Menendez brothers’ therapist didn’t face consequences?” They’re a bright bunch.

They are astutely looking into a world where the structures don’t reflect the guidance of best practices - the professional standards have been lost in the practical application, in many regards. If we know, for example, that suicidal risk is higher at discharge from involuntary hold in a hospital than at intake - shouldn’t we see that applied? Are the hobbyists among us the ones utilizing tools from 1990?

Let’s look over at our engineers in the room. While we, mental health professionals are biting our cheeks about our white coats - surely they feel more firmly grounded in their practice. Engineering would never come under fire as a hobby, especially when discussing contracting companies that drill the lines for gas wells! But, how well has professionalism protected consumers? If these things are available or possible under a profession, how well do things align? In plain terms, just because engineering shouldn’t be derived from tradition or guesswork, how often is that the case?

What’s the Harm?

If a profession is meant to be a public good through altruism, how much harm is allowable for overall progress? What would be the allowable amount of harm for a mental health professional operating misinformed or outside of guidance? We all draw the line at loss of life. How many client suicides are acceptable per 100,000? If that question churns your stomach, it should. The answer most professional mental health service workers are ready to give is “none.” However, are we functioning at that capacity? How sure are you that we are not producing harm unseen? Suicides in America have been the highest on historical record in 2022 - 2023; clearly, something is going wrong somewhere.

In engineering, I would hope the answer would be the same: no fatalities are acceptable. However, the numbers disagree. the Bureau of Labor Statistics estimated 5,283 work injuries in 2023, and annual fatalities at around 5,000 over the last ten years. Additionally, the construction industry reported about 1,000 deaths in 2023. OSHA estimates that in 2023, the rate of work fatalities was approximately 3.5 per 100,000 full-time employees. This is not including the notable engineering disasters in the public eye, such as the Florida International University (FIU) pedestrian bridge collapse (2018) which killed six. This also does not include the long-term consequences of engineering mistakes, such as the train derailment in East Palestine, Ohio, where the health consequences for the public remain to be seen. If the compromise is that some, always, will be in harms way - how many are you willing to sacrifice?

Oversight, or Out of Sight?

The point, here, is that professionalism does not protect the consumer, it protects the professional. You would not have questioned engineering, even if you were willing to question therapists. Now, why would either of those be immune to scrutiny? Expertise is a cloak of invisibility from accountability; our regulatory boards have a vested interest in furthering every field - they would not exist without them.

The recurring issues which create maritime and industrial disasters in the last 50 years are not specific to these industries alone:

Process safety failures and poor hazard analyses. Often, contractors, supervisors, or managing entities fail to conduct proper risk assessments or follow process safety management (PSM) standards. In more general terms, the guidance is there, and people fail to plan for risks of their work.

Deficient maintenance and aging infrastructure. Poor upkeep, ignored inspections, or outdated designs often don’t meet modern standards. A pipe that hasn’t been replaced since 1960 will age poorly, especially under new knowledge of best practices.

Flawed engineering design and miscalculations. Sometimes, unfortunately, things are screwed from the start. People get over ambitious while being under informed (check out the FIU bridge design issues) and this leads to an inevitable issue that is passed along to time and other leaders.

Human error and mismanagement. This is fairly self explanatory: poor decision-making, lack of training, or failure to follow (or write down) procedures. Yes, that phenomenon in corporate America of, “the new guy will figure it out, no one has time to train him,” happens even at major oil refineries.

Regulatory failures and lax enforcement. Sometimes, even regarding engineering - the people with the knowledge are not the people with the power to make or enforce regulations. Often, the right hand doesn’t know what the left hand is building.

Material failures and supply chain deficiencies. Poor quality materials, defects, or issues getting what was needed.

Our work in mental health services are vulnerable to these same failures - no matter how we defend the professionalism and expertise of our science. If engineering is susceptible, so are we.

Our process safety failures are poor clinical oversight and judgement. We also fail to properly assess and plan for risk. We over- or under-estimate suicidality, we rely on non-evidence or misunderstood interventions, we dismiss client viewpoints. Even if you pinky-promise that you don’t do those things - I know you can name someone who does.

Deficient maintenance is relying on old practices that have long since been updated, debunked, or criticized. We get burnt out and keep practicing because it’s our paycheck - the equivalent of falling asleep at the helm of a fishing vessel because the last run didn’t yield the pay that the crew needed. Sometimes, it’s even the lack of “maintenance and follow-up.” Yeah, many of us were trained to provide follow ups with clients that never come because of funding, time, attrition, or policies of our workplace. Do you always feel like people leave with everything they need to progress on their own with no further intervention? Is your machine…well-oiled?

Flawed design is flawed design, no matter what industry you choose. Our agencies rely on inefficient processes, eligibility and bureaucracy we try to skirt around, and build-the-bridge-as-you-walk-across-it modalities.

Human error and mismanagement is something we are more vulnerable to than engineering, so I hesitate to even provide examples. We misdiagnose, we make poor decisions about discharge or treatment level, we cruise through continued education credits because we’re busy and tired. Did you know engineers have continued education requirements too?

The regulatory failures relate to weak accountability in our field. Clients often don’t report ethical violations when they occur because they are disempowered. Funding fraud and systemic racism all happen in our fields! I have heard more offensive things come out of colleagues’ mouths than most clients. Just because there is a complaints process or a HR department, doesn’t mean

anything will happen except you getting called a “naive intern.”

Finally, material defects and supply chain issues are easy to see within our research biases and our funding issues. Psychotropic medications like SSRIs (zoloft, for example) have plenty of critiques, even beginning with the clinical trials that told us they were safe and helpful. If your materials, whether medication, treatment, or tools are defective, we are not rising to the standards we expect for ourselves. This applies even to the simple and often weekly occurrences that we take as inevitable like being left without the resources you need for public-facing events, teaching, or working with children. Many clinicians learn to work without or pay for their own supplies - and we know that the supply is minimal throughout the field.

Failing Upwards

These are not new issues in either field. However, we have to pump the breaks and review our histories. Many of us have been beguiled by the perceived power of expertise - even if that is allegedly the power to help or change the system. Can you even see the system from where you’re sitting? If engineering can fall to issues like having unqualified people in important positions, why couldn’t your field?

In the 2005 BP Texas City Refinery Explosion, some executives have minimal engineering expertise, but were making cost-driven decisions about important safety processes. In offshore drilling, the regulatory oversight allowed for managers on the Deepwater Horizon to have minimal experience with blowout risks. One of the worst environmental disasters in U.S history, and it’s partially accounted for by underprepared staff. Untrained, miseducated, or nepotism-appointed staff with control over major decisions. The stakes are high there in obvious ways, so why would mental health care be immune? It’s people’s lives no matter how you spin it.

Cost-cutting, shady contracting, deregulation and loopholes - these are issues of our larger systems, not specific fields. Our roof is leaking! We, as a nation, have not progressed to the point that we can foolproof any industry. Mental health practitioners need to understand that our “professional” titles do not give us an umbrella, and they do not give us a permit to reshingle until we can identify where those leaks are - and they’re not just in our portion of the floor plan. As mental health consumers, it is vital that we understand that we are in the basement. That leaking is felt most at the lowest floor.

The Steel Lining

Disasters have shaped engineering for the better - we have the opportunity for safer and smarter designs. Like most things, there are people much smarter than me working on improvements. That doesn’t mean we’re in the clear though, especially in mental health services.

We have to ask, have we learned from our disasters? As people, professionals, and mental health consumers - are we informed on our history and missteps? Be honest, do you know what your company’s land acknowledgement statement is about, or did you just mark that email as read? Have you looked around to find the ripple effects of policy changes in recent years? If so, do you know how those policies build from historical context? Politics is an inherited institution, after all. Unfortunately, if you’re going to call yourself an expert and make decisions that affect (and risk) people’s lives and wellbeing - you need to be an expert. This means learning every day, not just when you have to re-up your CEUs. As consumers, have you looked at information about your medications that isn’t from your psychiatrist? Have you asked critical questions about your treatment? Have you confronted your therapist when you feel you’re not making progress? I put much less onus on the consumers, but in many regards - professionals are both.

Ethical leadership and practical expertise are needed. As a professional, it is important that you do not except HR’s answer for major violations. If you see inefficiencies, errors, or ethical violations - it’s past due for you to speak up or fight for a promotion. If you are already in a leadership position, how hard do you work to be a leader? Are you a leader in title or in performance? What resources have you relied on to define your leadership values, styles, and beliefs?

Change starts with accountability. As a human being seeking mental health and wellbeing for yourself or others - are you ready to refine your truths and hear answers that you don’t like? How much humility do you have to spare?

For clinicians, the challenge is clear: as engineers must design with safety in mind, you must work with accountability in mind. You must be deliberate and calculated with your treatment - that means no more “kitchen sink” approach with no thought. Question outdated models, prioritize patient autonomy, and advocate for reform before the harm. If your gut response is, “but I already do that!” Then look for more room for improvement. Remember that we are still under the same roof.

For consumers, remember that mental health care is something you engage with and not just something you receive. You deserve clear, honest communication, collaboration and transparency. The science of mental health is not engineering - we do not have clear or perfect answers. Don’t accept a simple, unwavering answer for any of these human issues. Just as we demand safe bridges, we should expect safe and effective mental health treatment. Your voice, whether through questioning, advocacy, or sharing your personal experiences - are a vital force for making a better system.

Not radical, just refreshed.